It always feels like art fairs, such as Frieze, take more than they give. They are maximalist experiences, overloaded with spectacle and noise, whereas studio visits are minimalist, intimate, and often fragile. The irony is that when an art fair comes to town — a little like a circus or sideshow — artists often follow, or are dragged along, and that can lead to studio visits. Yet the intense, feverish energy of the fair, charged with false promises of fame, money, and truth, tends to leak into the studio. The fair frames and fuels the visit, and everything becomes infected with its urgency and superficial glare.

On a recent visit, my guest arrived visibly pumped. After half an hour of art-world gossip, we finally had to confront the elephant in the room — the work itself. It’s always a difficult bridge to build when the visitor makes or exhibits work very different from what they’re looking at. Ideally, both sides start bridge-building and meet in the middle; in reality, one tends to race ahead while the other hesitates, becoming the spectator in the room.

The visitor slumped into the only comfortable chair, ghost-like under its dirty sheet, distracted by last night’s booze and the endless stream of images flickering across his phone. He hadn’t really looked up since his first introductory monologue. You could almost see the party invites and private views reflected in his pupils. Every so often, he’d glance up and say things like, “I love it,” “Keep going,” or “Do more!” These didn’t feel like platitudes exactly, but they didn’t feel like real engagement either. The takeaway seemed to be: “I like where this is going, where you’ve been, but it’s not really my thing.” Later, as I was driving him to the next opening, we stopped at a red light — and he got out at that one.

The next day, I was back at Frieze myself. The crowd felt like a sea of Argos level paparazzi — even if only for their own Instagram feeds — each visitor photographing what they agreed with. I thought about the studio visit and realised I was doing the same thing. I was looking for work that fitted my own values and aesthetics. I wanted confirmation — to see my careful mix of concept, art, and psychology reflected back at me. Here I was, pretending to discover new work but actually just wandering through the fair, searching for validation rather than encountering work on its own terms.

Why couldn’t I, as yesterday’s visitor seemed to suggest, judge the work by reading its history — by seeing how it had developed into something original, even if it wasn’t ‘my thing’? Why couldn’t I take pleasure in watching a work form its own language, one I could learn to read because it was teaching me how to see it? Would it be possible, I wondered, to move through an art fair and see each work in the context of its own world rather than my own — to bring curiosity instead of personal, cynical judgement?

Why are we all obsessed with defending our own set of values — insisting there’s only one way art should move forward, only one lens through which it can be understood? It mirrors how we see the world itself: we conform to freedom, but only our version of it. We all know there are hundreds of routes, hundreds of art worlds, yet we still insist on our way or the highway.

Art fairs should be the perfect opportunity to test this openness — a mirror of the art world, a hotbed of discovery and serendipity. But in practice, every element that could support real engagement is lost. The context is commercial, not academic. The atmosphere is like a crowded nightclub with great wallpaper, where you barely know the people you’re shouting at, not the quiet of a gallery where the work can breathe. No artist makes work to be shown at an art fair. The space rarely complements the work. The gallerists, understandably, just want to survive the weekend — financially and mentally.

It’s difficult to stay open when everything around you is closing you down.

And yet, despite all this, perhaps Frieze has given me more than it has taken. Through the fog of hangovers and hurried studio visits, I’ve stumbled upon a quieter, more generous way of looking — one that might just outlast the concept of the art fair itself.

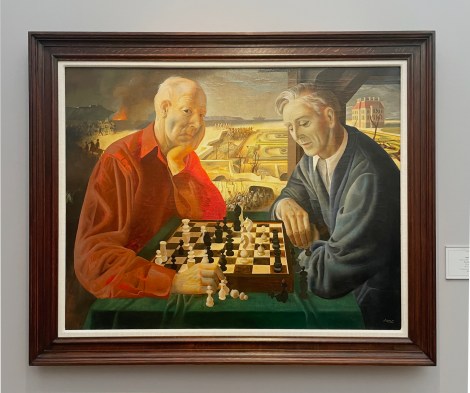

Image : Eppo Doeve, The Chess Players, 1946 at Frieze Masters 2025