The institutional tiles beneath my feet screamed public swimming pool, and if that wasn’t enough, the huge red hole—like the orifice of some great beast—presented itself to me. The echo of children’s screams spilled from inside the glowing plastic trumpet. The hallowed space of the 1990s water park was calling.

I was wasting time—daydreaming as usual—while trying to gather my New Year notes. List writing, editing, and rewriting is one of my main pastimes. I spend more time doing this than any other part of my practice. Why? Sections lead to lists, lists lead to projects, projects lead to new sections. They form an interlocking map of ideas, constantly wavering between procrastination and efficiency. At what point do notes and lists stop being signposts to work and become work in themselves?

There’s no feeling like being in a public swimming pool in the early 1990s. The clammy cold warmth, strangers’ bodies, the endless parade of counters just slightly too high to see over. Flip-flops and discarded towels, stray plasters and rubber key bracelets.

My local Midlands pool, minutes away from Birmingham’s notoriously tangled Spaghetti Junction, was also blessed with a terrifying high diving board and waterslides of various speeds, sizes, and angles. Even as a memory, I can taste the tepid, chlorinated water.

As I wait in line on the stairs for one of the slides, I dream not of the Space Invader crisps and soft drinks that awaited me at the end of the ride—the gold I’d been imagining on the drive there—but of potential dangers. Jagged edges of plastic, where fibreglass sheets are joined, stare at me like paper cuts, waiting for the opportunity to slice my innocent, exposed skin. Each step up gives me a new perspective, a new chance to turn back. And once I’ve entered this dark, liminal space, what could possibly be around the corner? Who knows—the tunnel disappears after only a few feet, a tunnel I know must leave the building to return, hopefully, into the plunge pool. How could something like this possibly exist? How could someone make this? What engineer, what architect, my raw child mind asks itself, could have created such an octopus monster, a suburban Kraken?

I tell myself I make lists to create green spaces. These spaces are times when I can work on a project; everything else in life is dedicated to creating them. They are periods when all the art is made—this, now, this moment I write, is a green space. They are not just times when I make a sculpture or write something; they are spaces sculpted and formed by everything that went into making them: the amount of money I could make, the materials I could find, the space I work in, and of course the ideas that go into them. These lists are the tubes that lead to the green space. They provide the psychological framework within which the work is made. Each and every time, I try to list the way I got there, to preserve the journey, to hopefully replicate it next time. It’s like trying to create a map from the present moment to the work, to a future me, which of course then becomes the present moment.

To get to the top of the Hydrofume—the name given to the slide that incorporated both a trip outside and a vertical drop—I had to walk up painted concrete steps, covered in a slim rubber mat to prevent accidents. Strangers revealed their personalities as they passed: some with confidence, others with trepidation, all different heights and weights, all in tight, colourful Speedos. At around eleven years old, the only time I saw a stranger’s semi-naked body was on television—a time before the internet, even before Page 3, when kissing was more familiar when done to an extra-terrestrial than to other humans. In the early 1990s, tattoos were rare and always darkly exotic. All I knew of them was that they reminded me of lists and science diagrams, combined with a dark foreboding probably brought about by Robert De Niro’s painted torso in Cape Fear. They seemed like strange labels, lists pointing towards hearts and bones, sailing ships and ropes.

Tattoos are made under the guise of signifiers: they are meant to mean something, to point to something else, whether that meaning is deliberate or not. Most often the message travels from the outside inward—from naval tattoos like Hold Steady across the knuckles to personal relationships, birth dates, or simply mum. They seem to point towards the heart. Somehow their meaning is created through a kind of biological osmosis, as if ink pumped through the dermis, combined with blood, could take the outside world of words, images, and diagrams and push them closer to the heart—the resting place of the soul.

These are thoughts I have now as I think of myself, arms crossed, hurtling through a small plastic tube. I remember even then being aware of the thickness of the plastic—so thin that light shone through it. This membrane was my second skin, protecting me from the outside world. Freefall, turning, completing a circle, then re-entering the building. In the warm, intestine-like interior, I anticipated—or imagined—the cold outside world. I screwed my eyes shut, praying for the experience to be over, for the destination to be reached. The internal scream—mum, are we nearly there yet?—reached new watery lows.

I look back at the computer in front of me. The twists and turns of lists give way to more lists—where do they point? Like the plot of a bad sequel to Memento, it quickly becomes unclear what state of mind I was in when I made one list or another. What was my intention? Wasn’t there a decision two weeks ago to relabel everything, to date it all and put it into more specific folders? When I made that alteration—did I cross it off the list?

Or is this a list for a new work? Or a cautionary note about a person, a lover, an artwork, or a life? Or simply a to-do far removed from art altogether? Like De Niro’s movie tattoos, they are fake—notes designed to distract, empty characters written for a backstory that was never pursued, a work never resolved.

The blood rushes to my head as water swooshes and sloshes in my ears. The final vertical drop approaches. All thoughts and ideas, plans and rules, past and future are shaken inside the plastic tube—a godlike test tube, a cocktail shaker with memories for ice cubes. Words rush forth, pathways coalesce, then suddenly, when the mind can take no more, I reach the bottom of the ride, the end of the list. I have entered the Green Space. The destination. All is peaceful. The actual work can happen. I have skin in the game.

For a few moments I am suspended in bliss. I am in my green space—underwater. But within a few seconds in the plunge pool, or a few hours in the studio, it is over. I can’t breathe. I must, at all costs, find air. I bolt upward, swimming for my life: towards civilisation, towards a job that needs to be done, messages that have to be replied to. The real world rushes in. Before I know it, I’ve crawled out, back to reality. Cold, humid, recycled air fills my lungs. Gravity takes hold. My body shifts from suspension to feeling… reality hits. And that’s it. It’s the end.

There’s nothing else to do but climb the steps. Choose another tube. Make another list. Go again.

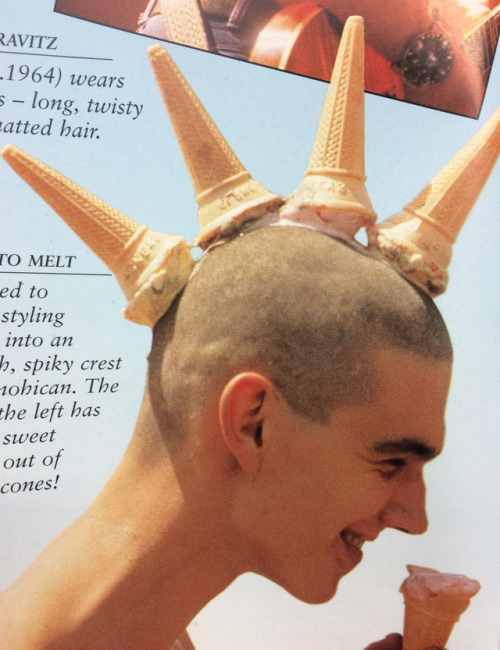

Image : Sandcastle Waterpark, families in the wave pool, Blackpool Gazette, 1987