Recently, someone failed to respond to a personal message that I had spent some time writing. I hadn’t spoken to them in a couple of years, but they had been an important part of my life, if only briefly. As time went by I started to get a creeping feeling of uncertainty, of being in limbo, helpless, suspended in anxiety — a feeling we’ve all grown used to, though it has become more prevalent and often tied to anxiety since we started using the internet as a kind of mirror. A mirror that doesn’t answer back, but instead presents us with heightened, often unwanted or unrealistic desires.

This unanswered desire, this creeping uncertainty, is a feeling artists know too well. It is a key essence of art-making: the uncertainty of which direction to go in, of whether what you’re doing has any value, how it will be received, if the work will ever be shown. Artists have to live in a state of constant uncertainty and delayed gratification. If they don’t accept this, they cannot fully engage in their practice. If they resist uncertainty, they often fall back on the rules of design or advertising, making art that fulfills a function rather than exploring unknown possibilities.

I think this feeling has deep roots in Western culture. The madness of endless productivity has trained humans to get used to absence and loss; the machine discards people. Think of how many people simply disappeared in war, or just walked out of a house — never to return. I think of the moment in The Grapes of Wrath, where Tom Joad leaves, simply disappears. In the narrative, it is to join the larger cause, the class struggle. But to me, as a teenager, it was just the raw experience of loss. I just couldn’t get over how you would build up a character like that just to dispose of him, metaphor or not.

In the 21st century, technology allows us to be found and tracked at all times, yet this very ease of connection has paradoxically increased loneliness and uncertainty. The easier it is to reach someone, the less we actually do. Could it be that we miss the real loss of someone — this feeling of disappearance that we have been socialized over the centuries to accept — so much that we’ve had to invent substitutes: ghosting, breadcrumbing, orbiting, submarining, or benching? In simple terms, psychologically weaponizing the act of disappearance.

I think artists who have trained themselves to live in this uncertain state are in a unique position to deal with it. They are disassociated from fixed aims and goals and can see uncertainty as a healthy, mindful state, turning it from fear, shame, or anxiety into a creative state of mind. But to do this, we first have to see it and label it as a natural part of the human condition — day-to-day life. We must be comfortable sitting in the darkness, knowing that no response may be itself a response, but also a mirror back to the original question, and that questions are sometimes worth asking, even without answers.

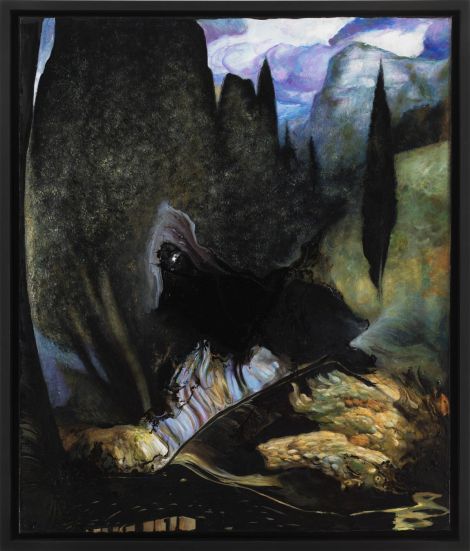

Image : Rachel Rose, Pitch Black Verdigris Green, 2022

Well said. XMike